The best companies win not by taking bigger risks, but by knowing something others don’t and using it well.

Most companies think that strategy is about managing risk. It’s not. It’s about knowing something others don’t.

To be sure, business is risky—painfully so. Nearly half of all new businesses fail in their first five years, and up to 95% of new product launches are doomed. Yet, in the midst of all that carnage, some leaders win consistently by spotting and acting on opportunities that others miss. How do they keep beating the odds?

One of the biggest and most enduring corporate myths is that great companies and leaders win because they’re willing to take bigger risks than others. But what may look from the outside like an appetite for risk is actually an ability to see things more clearly. They’re not gamblers—they’re making decisions based on insight.

Insight is a strong contender for the most overused and misunderstood word in business. Everyone wants it, and many claim to have it. Companies have insight teams and insight platforms. A growing number are now turning to generative AI for “insights,” based on the technology’s ability to scour huge volumes of previously untapped data.

When you scratch the surface, though, much of what gets labeled as insight is really just well-packaged observation. What’s touted as strategic insight is often just a rebranding of existing facts. Worse, many companies end up relying on the same “insights” that their competitors are seeing. The result is often a void of genuinely unique ideas.

Several years back, I was on a conference call with a group of execs at a health insurance company. The team wanted to launch a new offering to support human resources leaders in large companies. They wanted to make sure that the new program would be a success. “Great,” I said. “But what do we know about HR execs that no one else knows?”

The call went silent. No one said a word. A minute passed… still silence… I started to worry that we might have gotten disconnected. “No, we’re still here,” one exec said. “We’re just thinking…”

In their defense, a lot of people find themselves in that same situation: after gathering significant amounts of qualitative and quantitative research on customers and competitors, many teams are unable to point to something they know that no one else does. They have tons of research. They just don’t have any insights.

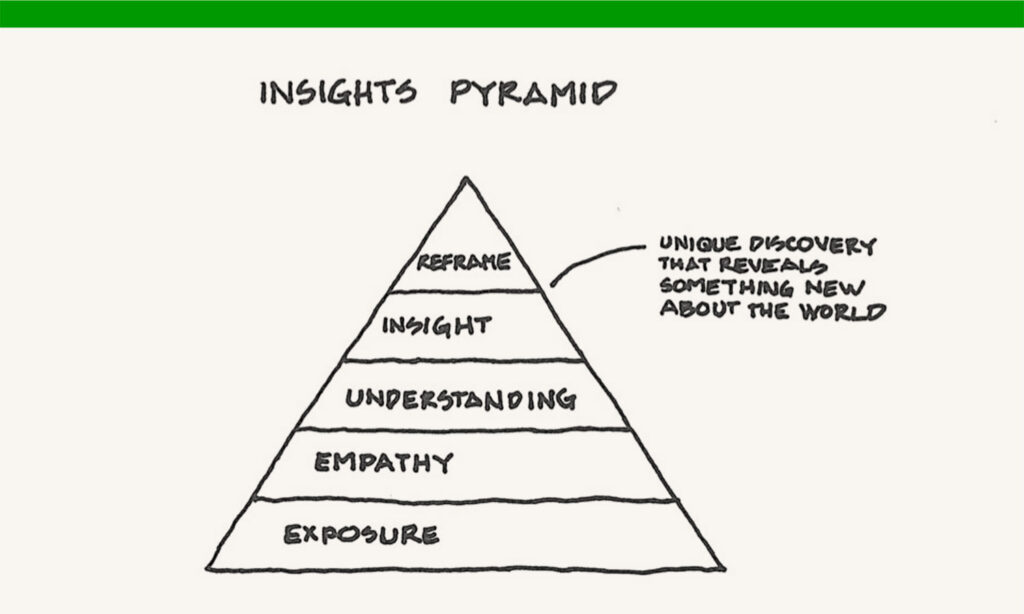

So, what counts as insight? And how do you get it? Over the past three decades, my colleagues and I at Jump have studied how organizations uncover genuine insights. What we’ve found is that not all insights are created equal. Most learnings about consumers, customers, and competitors exist at one of five levels, each one building on the next. And the higher you go, the lower your risk becomes—not because you’re playing it safe, but because you’re making smarter decisions.

Exposure: Seeing New Perspectives

The first level is exposure, when you get an initial awareness of something new about market conditions, the competitive space, or consumer behavior. It’s when you stop relying on second-hand information or hearsay and start seeing the world as it really is. This can often come from just spending a little time in the real world: visiting a customer, walking a store, or checking out a competitor. If your new mobile phone service is aimed at millennial Latinos, it’s a good idea to go meet a few millennial Latinos. Not in a focus group room, but where they actually live and work.

When he was Chief Information Officer of BayCare Health, Lindsey Jarrell used to send new IT hires to spend their first few days on the job at a nursing station in one of BayCare’s hospitals. Lindsey, who now leads HealthLink Advisors, knew that newcomers needed to see firsthand what it was like to be a nurse if they were going to build useful technology systems and tools for them. They needed to see the stress, the interruptions, and the frustrations.

Before she became CFO at Target in 2015, Cathy Smith took a road trip with her husband across the country. Along the way, they visited Target stores in every town they stopped in. By the end of their trip, Cathy had a good sense of how Target stores looked, what was stocked, and who was shopping. No research firms, consultants, or “insight platforms” were required.

This baseline level of exposure may seem simple, but many executives never make it this far up the ladder. They’re too caught up in the world of dashboards, PowerPoints, and Zoom meetings to make space for real-world perspectives.

Empathy: Getting a Feel for Things

If exposure is seeing the world, empathy is starting to get a feel for it. It means having an intuitive, lived sense of what it’s like to be one of your customers or partners.

While exposure can happen in an afternoon, empathy deepens gradually over time when you put in the hours to watch, talk with, and listen to people.

Nike has traditionally excelled at this. It’s a company run by athletes, for athletes. The people designing running shoes are often runners themselves. So even if their market research is off, their final product still ends up working because it’s grounded in an empathic understanding of the customer. Patagonia has developed strong loyalty among customers because they know it’s run by people who have climbed mountains, lived outdoors, and who value the environment. That contrasts with other apparel companies that lack a truly intimate connection with their customers.

The business advantage gained from empathy is having an intuitive vibe for what your customers need. You start to notice things faster than people who only read about it later in The Wall Street Journal. You spend less time in meetings with people arguing about what would be obvious if you were out in the world. This can lead to developing breakthrough products or services, going beyond the incremental advances that might result from exposure.

Understanding: Finding the Patterns

Once you’ve spent enough time out there, you start to see patterns. You can come to a level of real understanding. Understanding is when you move from an implicit to an explicit grasp of things—not just of what people do, but why and how they do it. Understanding often shows up in the form of customer segmentations, satisfaction surveys, and behavioral archetypes.

Delta Air Lines CEO Ed Bastian has made customer understanding a cornerstone of Delta’s transformation. He made tracking customers’ Net Promoter Score a top corporate priority for the company, using it as a barometer for how Delta was doing. NPS data became a critical tool to understand customers’ pain points and steer improvement across every aspect of the flying experience, from seatback entertainment to Wi-Fi connectivity to cancellations.

Hampton Inn has used understanding to become the world’s biggest revenue-generating hotel brand, and one of the most profitable. In a saturated mid-market bracket, Hampton’s leadership has managed to differentiate the brand through an obsessive drive to understand customers. Based on guest feedback, they switched to curved shower-curtain rods to give guests a little more elbow room and rounded the edges of beds to reduce the chance of shin-bumping incidents. After understanding that guests can be a bit messy and even forgetful, they started removing desks from rooms and doors from the wardrobes.

YouTube might not be what it is today without an early flash of understanding. YouTube’s original plan was to be a dating website, where people could upload videos of themselves talking about their dream partner. Analyzing usage data, YouTube’s founders quickly learned that women were far more reluctant than men to upload videos of themselves. But both men and women were happy to upload all kinds of other short videos that they liked. The company quickly pivoted away from dating, and the YouTube we know now was born.

Insight: Knowing What Others Don’t

If you spend time hanging out in the real world, if you gather significant amounts of data, and if you spend time rigorously analyzing what you observe, you might even get to a genuine insight—discovering something other people have missed. An insight is a nugget of something special or even proprietary—something that’s both true and not widely known. An insight can give you an opening to set yourself apart from competitors.

Financial management platform Quicken was born from a moment of insight. Founder Scott Cook came home one night to find his wife working to balance the family checkbooks. That sparked the insight that while finance professionals think in spreadsheets, regular people needed something more accessible and familiar—a money management app modeled on a checkbook.

Many years ago, we worked with Armor All, the maker of car cleaning products. At the time, the brand was trying to figure out how to grow beyond its core male audience. Using first-hand ethnographic research and significant data analysis, we found something surprising. For many people, the state of their home and their car said something about them as parents. If you had a clean home, you were a good parent. But if you had a clean car, you were a bad parent. It meant you were spending too much time focused on yourself, rather than focusing on your family. Often, Mom’s car was a complete mess of tissue boxes and sunscreen and Cheerios. And Dad’s car was spotless. Armor All’s consumer base wasn’t just highly gendered because guys like cars. Using Armor All products said something important about people’s identity as parents.

Reframe: Seeing the World in a New Way

Insight isn’t the end of the journey. Sometimes, multiple insights can lead you to a fundamental reframe of how you see the world. It’s the equivalent of taking the red pill in The Matrix.

Reframes don’t come easy. They can require deep, often uncomfortable research and letting go of old assumptions. But the payoff can be enormous. Reframes can create new behaviors and open up new markets, giving you a head start that’s hard to copy. This is particularly useful when your space is getting crowded or growth is slowing, and you need to do something different.

One of the most powerful reframes we’ve worked on came from a healthcare project on diabetes management. The core issue was adoption: diabetics weren’t using the apps designed to help them. What we learned was that the fundamental problem lay in the sentence you just read. All those apps treated people as diabetics, and people with diabetes don’t want to be diabetics. They don’t want a condition that they have to become their identity. Particularly for folks with adult-onset diabetes, they want to be normal people who just happen to have high blood sugar. And they will actively avoid engaging with products that make them feel otherwise. That’s more than just an issue of language. That’s a fundamental reframe. It changes how you design products, how you develop revenue models, and how you go to market.

Abbott Labs nailed this with their continuous glucose monitor, the Libre. The tiny sensor sits on your arm and doesn’t require you to draw blood. The product connects to an entire ecosystem of third-party apps focused on weight loss, metabolic health, and wellbeing—apps that have nothing to do with diabetes. Their newest version, Lingo, doesn’t even require a prescription from your doctor. It’s marketed to anyone who wants to understand their body a little better. And that just happens to include many people with high blood sugar. That’s a reframe.

How Big is Your Insight?

The ability to see the world differently is available to every leader. The crucial thing is to ask yourself and your colleagues what you know about a space that no one else does. Start by spending time in the real world, sitting at the proverbial nurses’ station, so you can couple whatever data you have with first-hand experience. Then ask yourself how your playbook needs to change to align with what you’re learning.

Each step on the insight ladder has value. But the higher you go, the more you reduce the risk of bold moves and start redefining your company’s place in the world.

If your competitors are all looking at the same dashboards, reading the same reports, and running the same models, then your advantage will never come from following that crowd. It comes from seeing something they don’t. From walking the factory floor. From sitting in the hospital waiting room. From hearing the unspoken truth in your customers’ stories.

The question isn’t whether you can find those insights. It’s whether you’ll make the time to do it. Because the companies that win aren’t the ones who take bigger risks—they’re the ones who make smarter bets. And the smartest bet you can make is to know something others don’t.

Time to get outside…

Dev Patnaik

Dev Patnaik